Agent design patterns

2025 ended with Meta buying Manus for over $2b and Claude Code reaching a $1B run rate. Here I explore common design patterns across these and other popular agents based on many of my favorite blogs, papers, and posts.

We are getting closer to long-running autonomous agents. @METR_Evals reports that agent task length doubles every 7 months. But one challenge is that models get worse as context grows. @trychroma reported on context rot, @dbreunig outlined various failure modes, and Anthropic explains it here:

Context must be treated as a finite resource with diminishing marginal returns. Like humans with limited working memory, LLMs have an “attention budget.” Every new token depletes it.

With this in mind, @karpathy framed the need for context engineering:

Context engineering is the delicate art and science of filling the context window with just the right information for the next step.

Effective agent design largely boils down to context management. Let’s explore a few common ideas from my favorite blogs, papers, and posts.

Give Agents A Computer

@barry_zyj and @ErikSchluntz defined agents as systems where LLMs direct their own actions. It’s become clear over the past year that agents benefit from access to a computer, giving them primitives like a filesystem and shell. The filesystem gives agents access to persistent context. The shell lets agents run built-in utilities, CLIs, provided scripts, or code they write.

We’ve seen this across many popular agents. Claude Code broke out as an agent that “lives on your computer”. Manus uses a virtual computer. And both fundamentally use tools to control the computer, as @rauchg captured:

The fundamental coding agent abstraction is the CLI … rooted in the fact that agents need access to the OS layer. It’s more accurate to think of Claude Code as “AI for your operating system”.

Multi-Layer Action Space

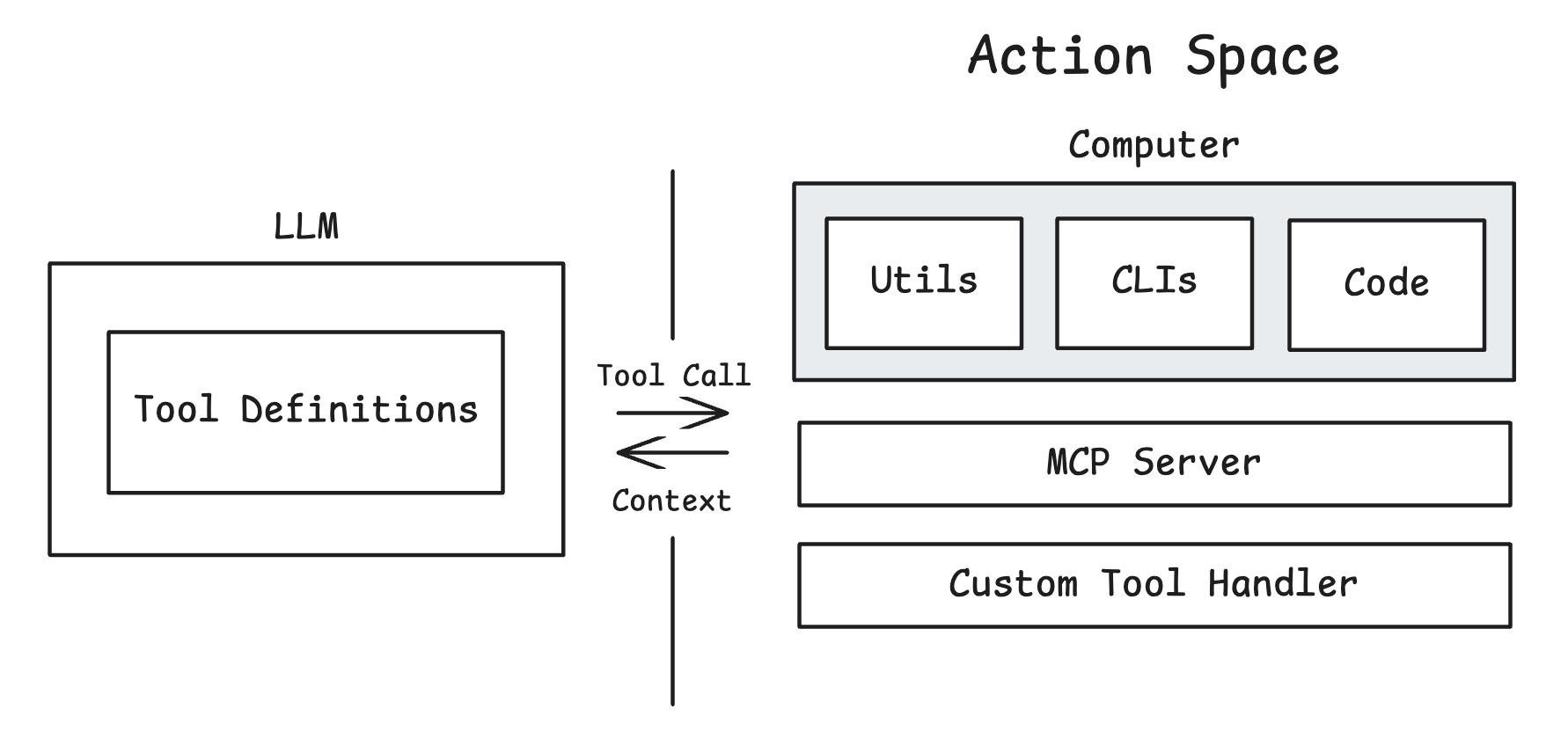

Agents perform actions by calling tools. It’s become easier to give tools to agents (e.g., via model context protocol). But, this can cause problems: As MCP usage scales … tool definitions overload the context window and intermediate tool results consume additional tokens.

Tool definitions are typically loaded into directly into context. The GitHub MCP server, as an example, has 35 tools with ~26K tokens of tool definitions. More tools can also confuse models if they have overlapping functionality.

Many popular general purpose agents use a surprisingly small number of tools. @bcherny mentioned that Claude Code uses around a dozen tools. @peakji said that Manus uses fewer than 20 tools. @beyang from Amp Code talks about how they curated the actions space to include only a few tools.

How can agents limit tools but still perform a wide range of actions? They can push actions from the tool calling layer to the computer. @peakji explained the Manus action space as a hierarchy: the agent uses a few atomic tools (e.g., a bash tool) to perform actions on the virtual computer. Its bash tool can use shell utilities, CLIs, or just write / execute code to perform actions.

The CodeAct paper showed that agents can chain many actions by writing and executing code. Anthropic wrote about this here, highlighting the token savings benefit because the agent does not process the intermediate tool results. @trq212 showed some practical examples of this using Claude.

Progressive Disclosure

An agent needs to know what actions are available. One option is to push actions to the tool calling layer and load tool definitions upfront into context.

But, we’ve seen a trend towards progressive disclosure of actions for better context management. This is a design pattern that shows only essential information upfront and reveals more details only as the user needs them.

At the tool calling layer, some agents index tool definitions and retrieve tools on demand, potentially using a search tool to encapsulate this process.

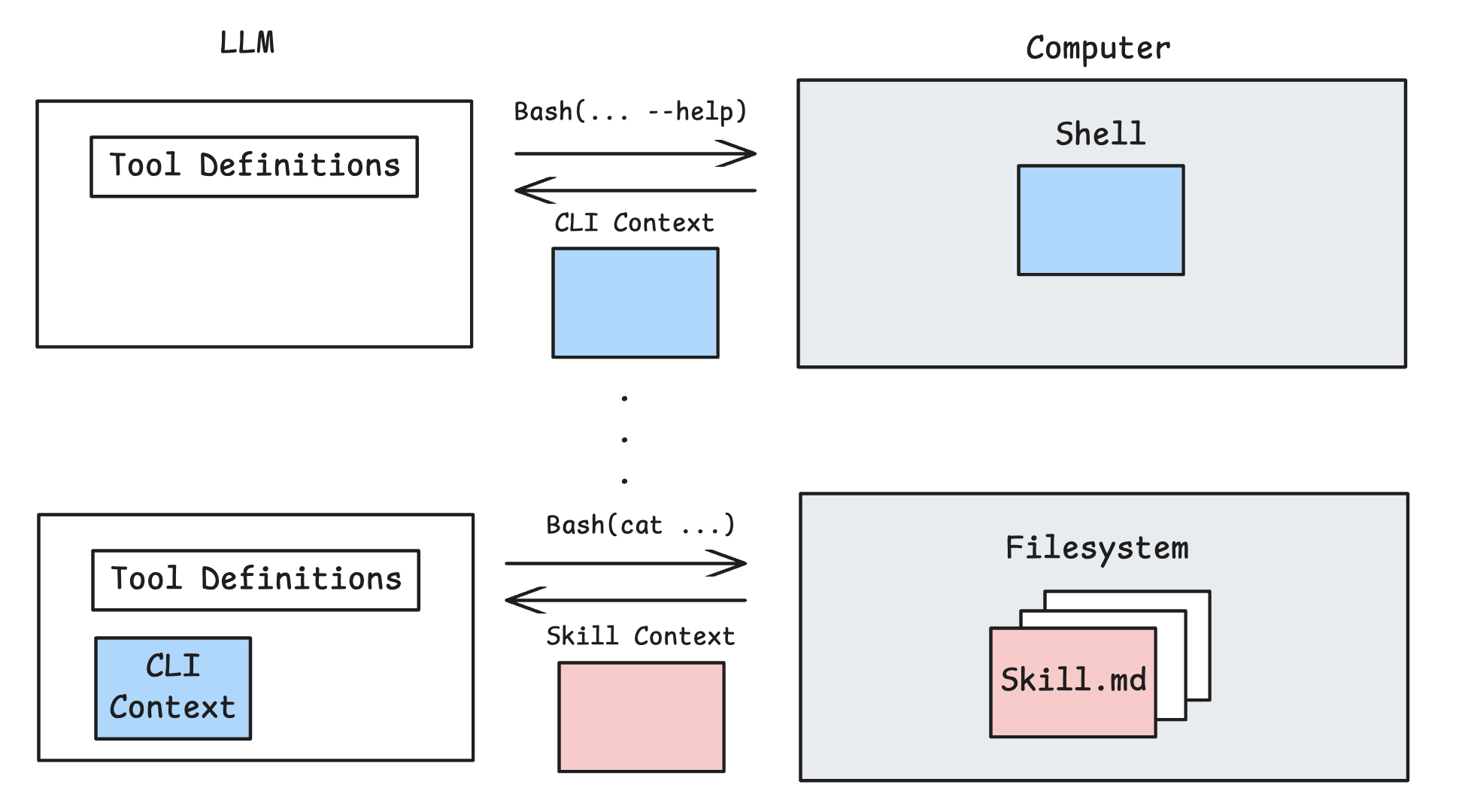

For shell utilities or installed CLIs, @peakji said that Manus just provides a list of available utilities in the agent instructions. Then agent uses its bash tool to call the –help flag (or similar) to learn about any one of them if needed.

MCP servers can be pushed from the tool calling layer to the computer, allowing them to be progressively disclosed. Cursor Agent syncs MCP tool descriptions to a folder, gives the agent a short list of available tools, and allows the agent to read the full description only if needed based on the task. Both Anthropic and Cloudflare discuss similar ideas for MCP management.

Anthropic’s skills standard uses progressive disclosure. @barry_zyj and @MaheshMurag gave a talk on it, which explains that skills are folders containing SKILL.md files. The YAML frontmatter of each file is loaded into agent instructions, letting the agent decide to read SKILL.md only if needed.

Offload Context

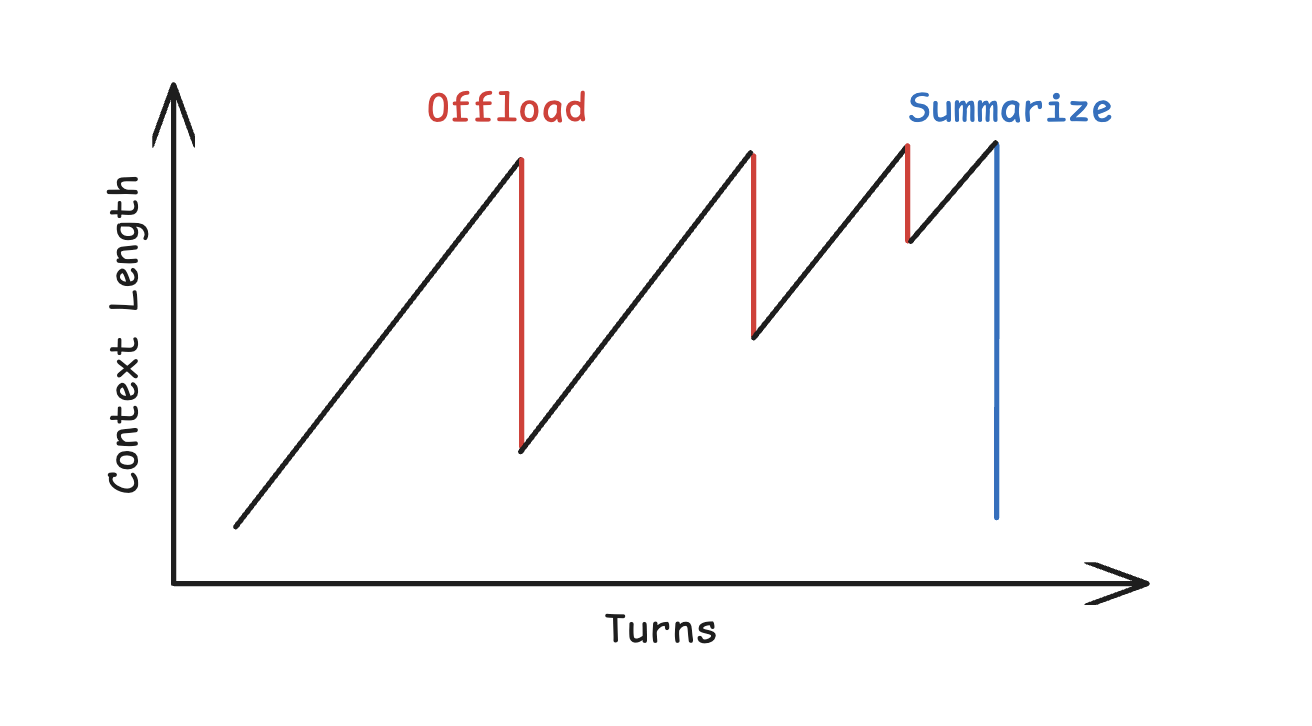

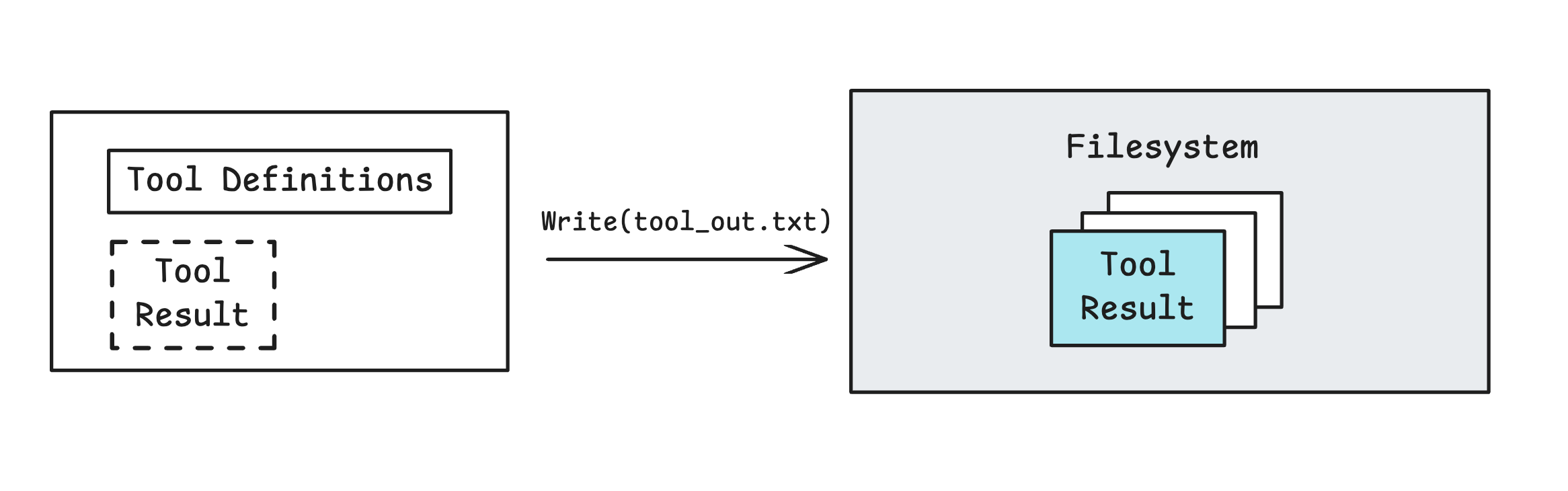

Another thing you can do with a computer is offload context from the agent context window to the filesystem. Manus writes old tool results to files and only applies summarization once there is diminishing returns from offloading.

Cursor Agent also offloads tools results and agent trajectories to the filesystem, allowing the agent to read either back into context if needed.

Both of these examples help address the valid concerns that compaction of context (aka summarization) can result in loss of useful information.

Offloading context to the filesystem can also be used to help steer long-running agents. Some agents write a plan to a file and read it back into context periodically to reinforce objectives and / or verify its work.

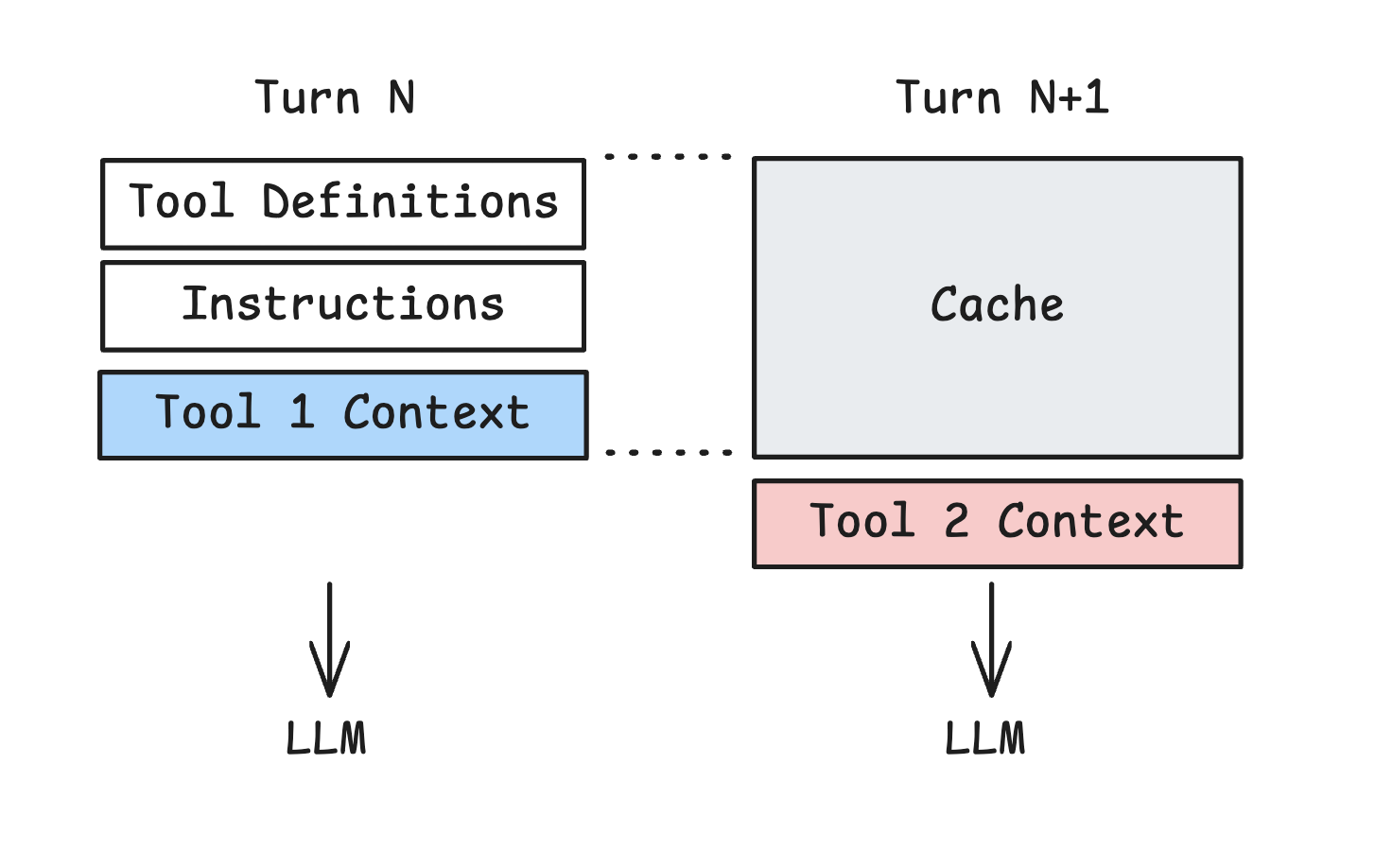

Cache Context

Agents typically manage context as a list of messages. The context from each action is just appended to this list. @irl_danB had an interesting comment:

Agents (use a) linear chat history. Software engineers … mental model resembles a call stack: pushing tasks on, popping them off (when done)

It is interesting to consider ways to mutate the session history by removing or adding context blocks. But, there is a consideration that informs how context might be mutated. Agents can become cost prohibitive without prompt caching, which allows an agent to resume from a prompt prefix.

Manus called out “cache hit rate” as the most important metric for production agents, and mentioned that a higher capacity ($/token) model with caching can actually be cheaper than a lower cost model without it. @trq212 notes that coding agents (Claude Code) would be cost-prohibitive without caching.

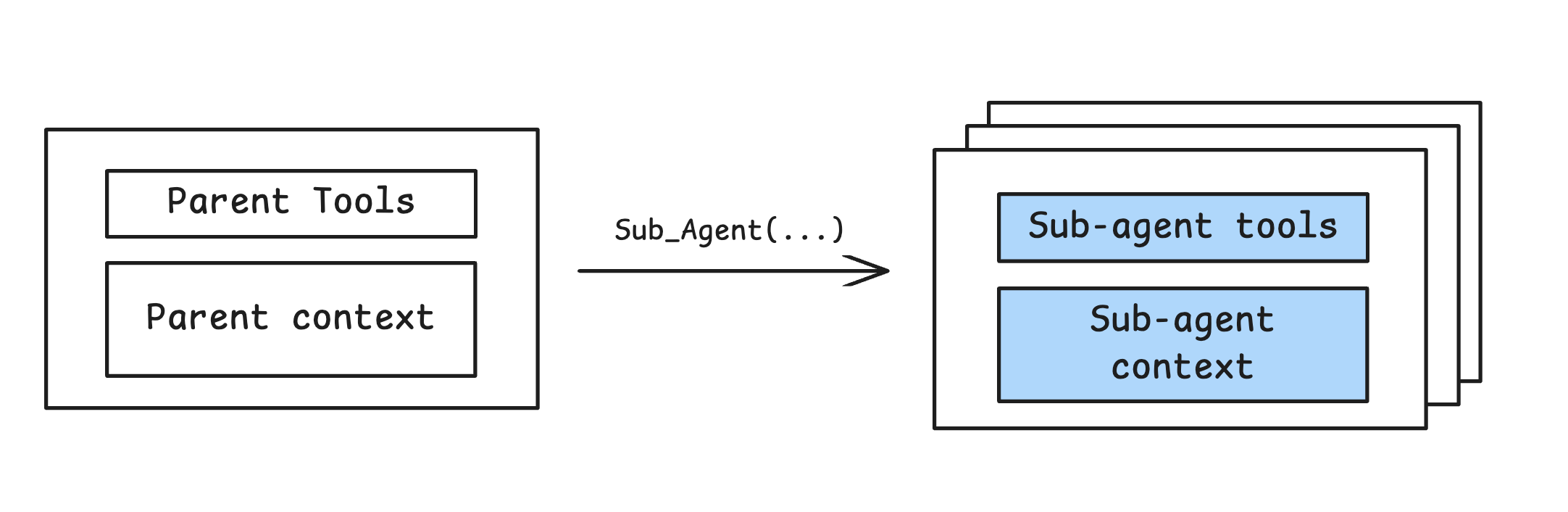

Isolate Context

Many agents delegate tasks to sub-agents with isolated context windows, tools, and / or instructions. A clear use for sub-agents is parallelizable tasks. @bcherny mentioned that the Claude Code team uses sub-agents in code review to independently check different possible issues. A similar map-reduce pattern can be used for tasks like updating lint rules or migrations.

Long-running agents also use context isolation. @GeoffreyHuntley coined the “Ralph Wiggum”, a loop that runs agents repeatedly until a plan is satisfied. It is often infeasible for a long running task to fit into the context window of a single agent. Context lives in files and progress can be communicated across agents via git history (see @ryancarson overview and @dexhorthy’s post).

Anthropic described one version of the Ralph loop where an initializer agent sets up an environment (e.g., a plan file, a tracking file) and sub-agents tackle individual tasks from the plan file. @bcherny mentioned this pattern with Claude Code, using stop hooks to verify work after each Ralph loop.

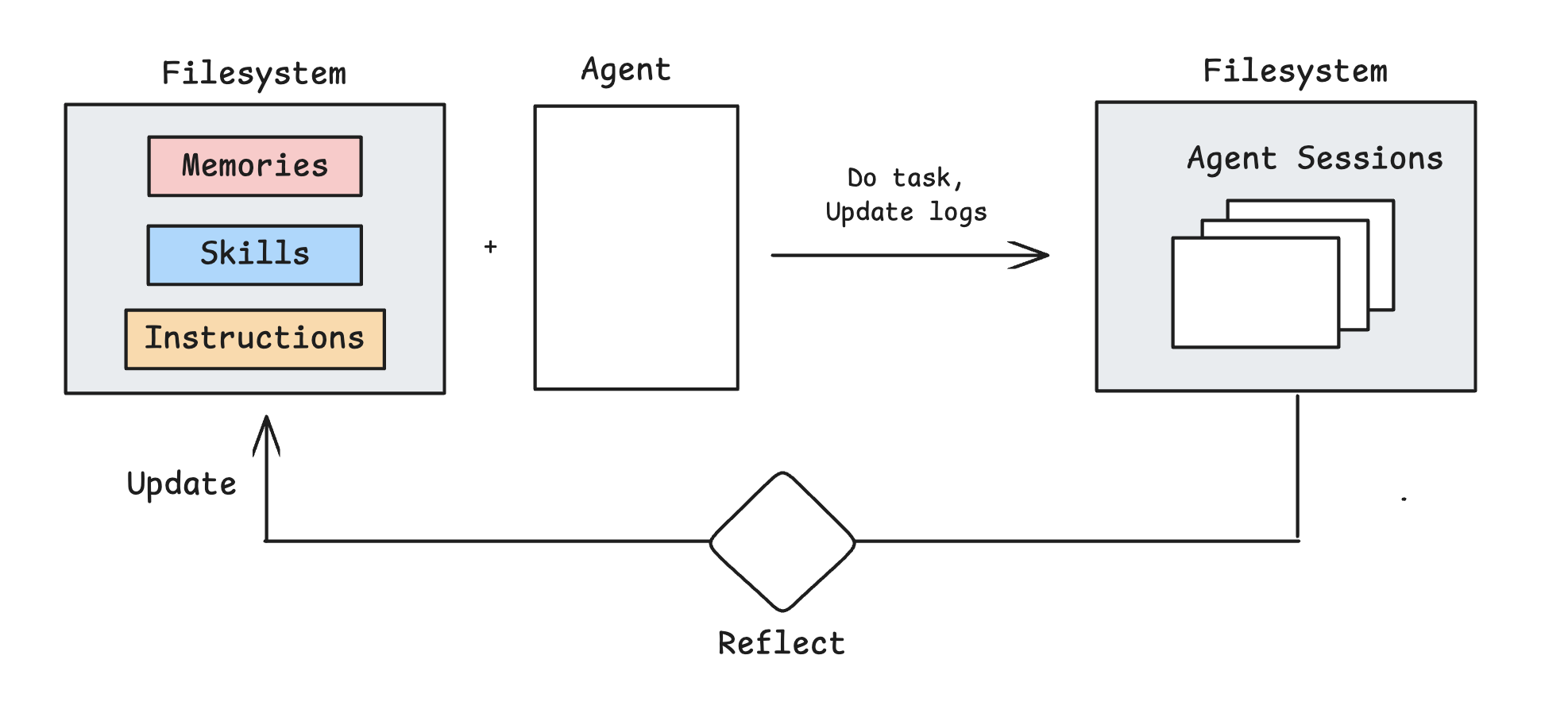

Evolve Context

There’s been a lot of interest in continual learning for agents. We want agents to improve at tasks and learn from experience, like humans. Some research has shown that agent deployments fail due to inability to adapt or learn.

@Letta_AI talks about continual learning in token space, which just means updating agent context (rather than the model weights) with learnings over time. A common through line across approaches involves reflecting over past agent trajectories/sessions and using this as a basis for context updates.

This pattern be applied to task-specific prompts. GEPA from @lateinteraction applies this: collect agent trajectories, score them, reflect on failures, and propose a mix of task-specific prompt variants for further testing.

This pattern can also be applied to open-ended memory learning. There’s many papers on this. I’ve tested it with Claude Code, inspired by an interesting insight from @_catwu: distill Claude Code sessions into diary entries, reflect across diary entries, and use them to update CLAUDE.md.

This can also be applied to skills. @Letta_AI has an example of this, reflecting over trajectories to distill reusable procedures and then saving them to the filesystem as new skills. I’ve tested similar ideas with Deepagents.

Future Directions

A few patterns have emerged. Give agents a computer, and push actions from the tool calling layer to the computer. Use the filesystem to offload context and for progressive disclosure. Use sub-agents to isolate context. Evolve context over time to learn memories or skills. Cache to save cost / latency.

There are many open challenges that I’m excited to track over the next year.

Learned Context Management

Context management can include hand-crafted prompting for compression, spawning sub-agents, determining when / what context to offload, and how to evolve context for learning over time. The Bitter Lesson predicts that compute / model scaling often overtakes such hand-crafted approaches. For example, rather than compaction @jeffreyhuber suggested an idea:

Recursive Language Model (RLM) work from @lateinteraction, @a1zhang, @primeintellect is a generalization of this point, suggesting that LLMs can learn to perform their own context management. Much of the prompting or scaffolding packed into agent harnesses might get absorbed by models.

This seems particularly interesting for memories. It’s a bit related to the sleep-time compute paper by @Letta_AI, which shows that agents can think offline about their own context. Imagine if agents automatically reflect over their past sessions and use this to update their own memories or skills. Also, agents might directly reflect over their own memories accumulated over time to better consolidate them and / or prepare for future tasks, just as we do.

Multi-Agent Coordination

As agents take on larger tasks, we will likely see swarms of agents working concurrently. @cognition noted that today’s agents struggle with shared context: each action contains implicit decisions and parallel agents risk making conflicting decisions without visibility into each other’s work. Agents can’t engage in the proactive discourse that humans use to resolve conflicts.

Multi-agent project like Gas Town by @Steve_Yegge are interesting: it uses a multi-agent orchestrator with git-backed work tracking, a “Mayor” agent with full context about the workspace, and coordinates dozens of concurrent Claude Code instances with a merge queue and role specialization. This and related multi-agent coordination efforts will be interesting to follow.

Abstractions for Long-Running Agents

Long-running agents need new infrastructure: observability into what agents are doing, hooks for human review, and graceful degradation when things go wrong. Today’s patterns are still rough. Claude Code uses stop hooks to verify work after each iteration and the Ralph Loop tracks progress via git history. But there’s no standards for agent observability, common debugging interfaces, or agreed-upon patterns for human-in-the-loop monitoring. As agents run longer, we’ll probably need new abstractions to manage them.