Learning the Bitter Lesson

The biggest lesson that can be read from 70 years of AI research is that general methods that leverage computation are ultimately the most effective, and by a large margin.

Rich Sutton, The Bitter Lesson

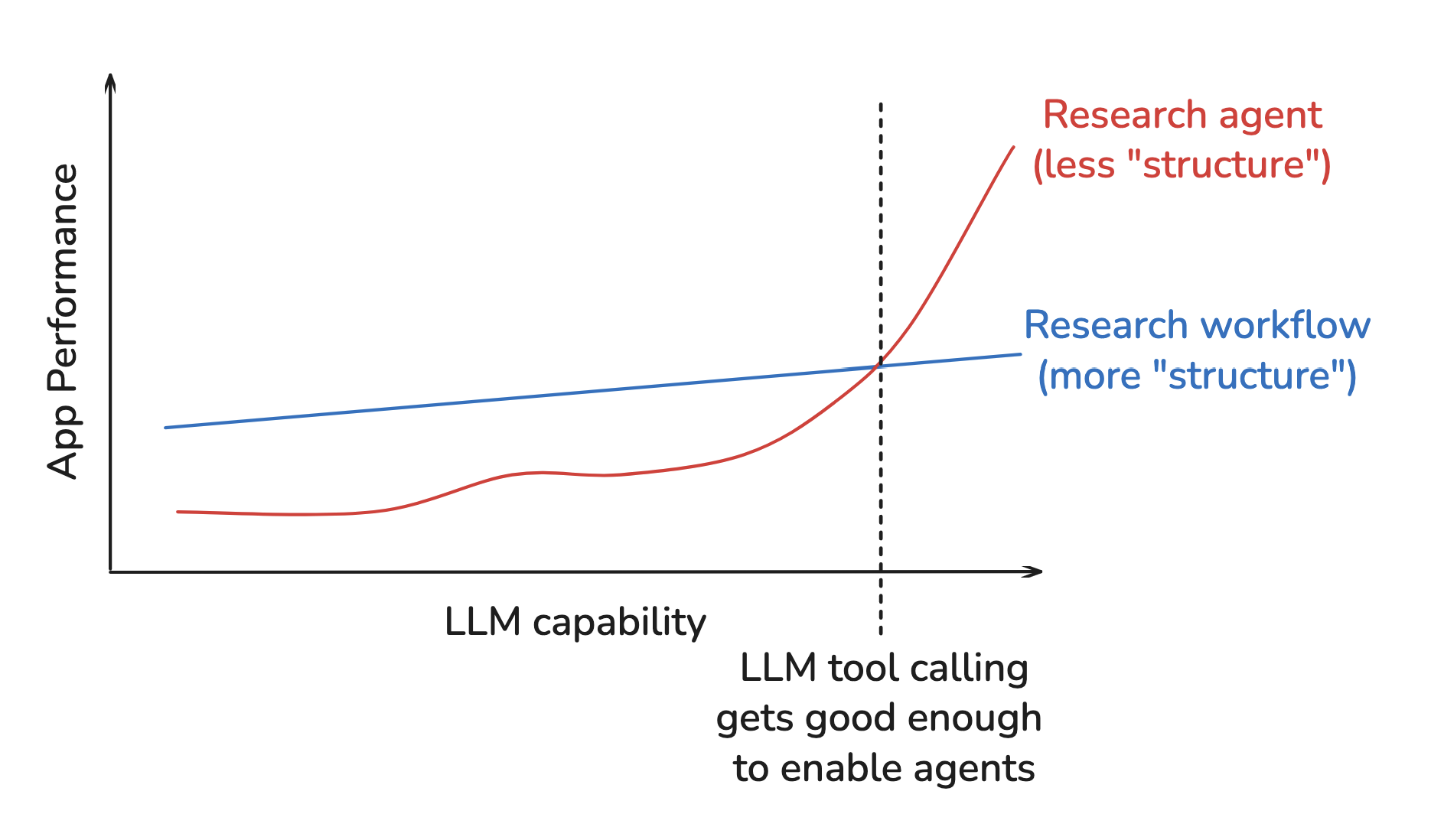

The Bitter Lesson has been learned over and over across many domains of AI research, such as Chess, Go, speech, vision. Leveraging computation turns out to be the most important thing and the “structure” we impose on models often limits their ability to leverage growing computation.

What do we mean by “structure”? Often structure includes inductive biases about how we expect models to solve problems. Computer vision is a good example. For decades, researchers designed features (e.g., SIFT and HOG) based upon domain knowledge. But these hand-crafted features restricted models to the patterns that we anticipated. As computation and data scaled, deep networks that learned features directly from pixels outperformed hand-crafted methods.

With this in mind, Hyung Won Chung’s (OpenAI) talk about his research approach is interesting:

Add structures needed for the given level of compute and data available. Remove them later, because these shortcuts will bottleneck further improvement.

The Bitter Lesson in AI Engineering

The Bitter Lessons also applies to AI engineering, the craft of building applications on top of rapidly improving models. As an example, Boris (lead on Claude Code) mentioned that the Bitter Lesson strongly influenced his approach. And I’ve found that Hyung’s talk provides some useful lessons for AI engineering. Below I’ll illustrate this with a story about building open-deep-research.

Adding Structure

I had frustrating experiences with agents in 2023. It was hard to get LLMs to reliably call tools and context windows were small. In early 2024, I became interested in workflows. Rather than an LLM autonomously calling tools in a loop, workflows embed LLM calls in predefined code paths.

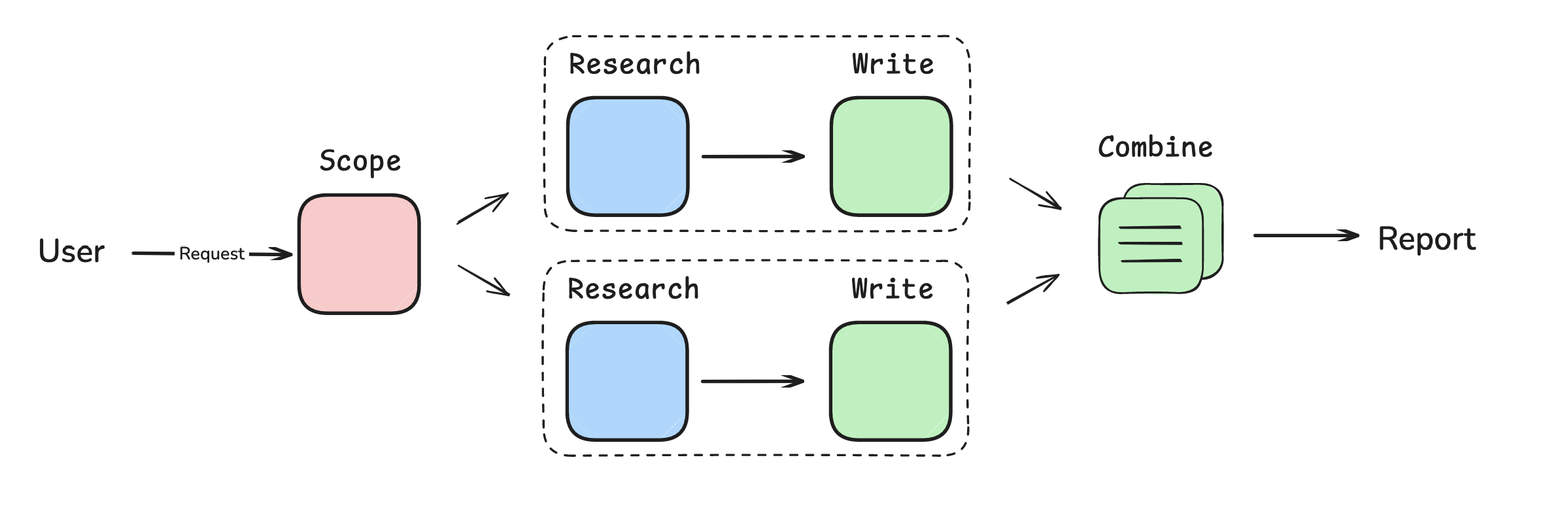

In late 2024, I released an orchestrator-worker workflow for web research. The orchestrator was an LLM call that took a user’s request and returned a list of report sections to write. A set of workers parallelized research and writing all report sections. Then, I just combined them together.

So, what was the “structure”? I imposed a few assumptions about how LLMs should perform fast, reliable research: it should decompose the request into a set of report sections, research and write them in parallel to make it fast, and avoid tool calling to make it more reliable.

Bottlenecks

Things began to shift as 2024 came to a close. Tool calling was getting better. By winter 2025, MCP had gained significant momentum and it was clear that agents were well suited to the research task. But, the structure I imposed prevented me from leveraging these improvements.

I did not use tool calling, so I could not take advantage of the growing MCP ecosystem. The workflow always decomposed the request into report sections, a rigid research strategy that was not appropriate for all cases. The reports also were sometimes disjoint because I forced workers to write sections in parallel.

Removing Structure

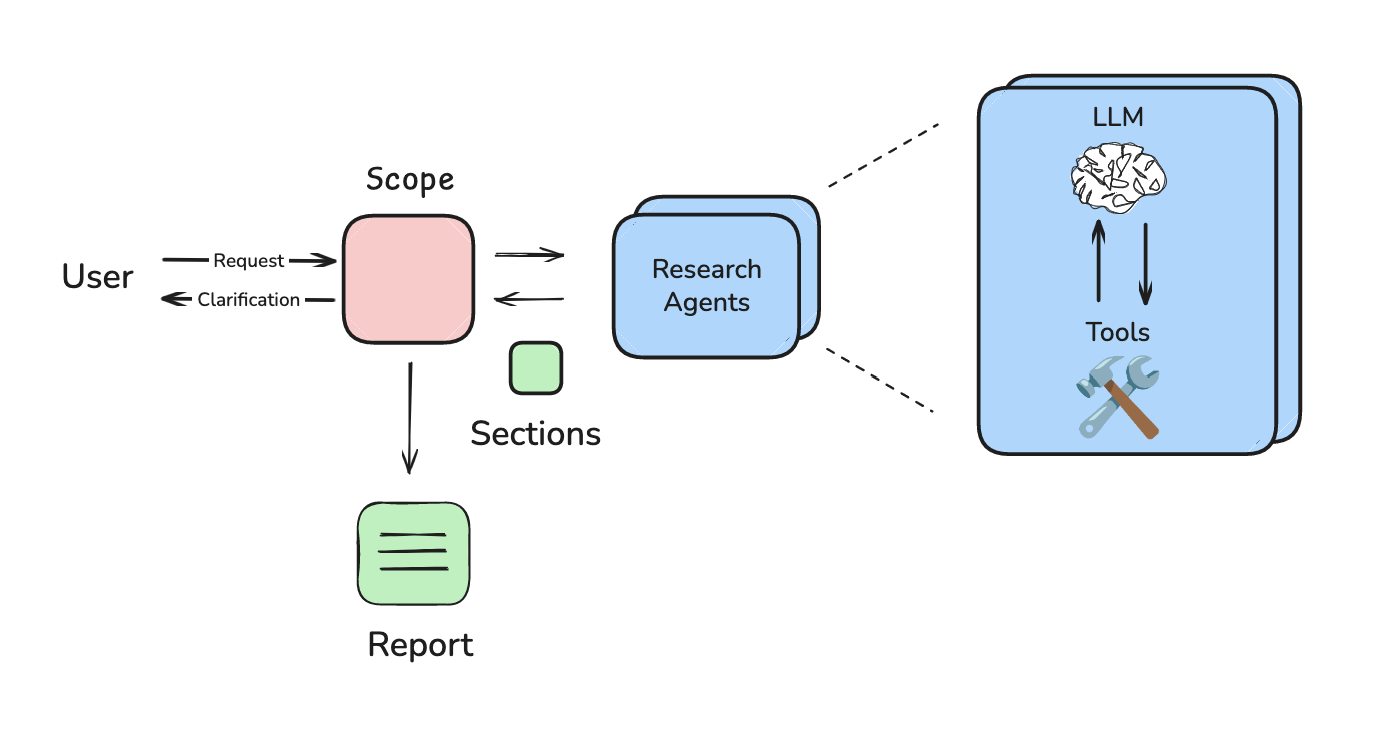

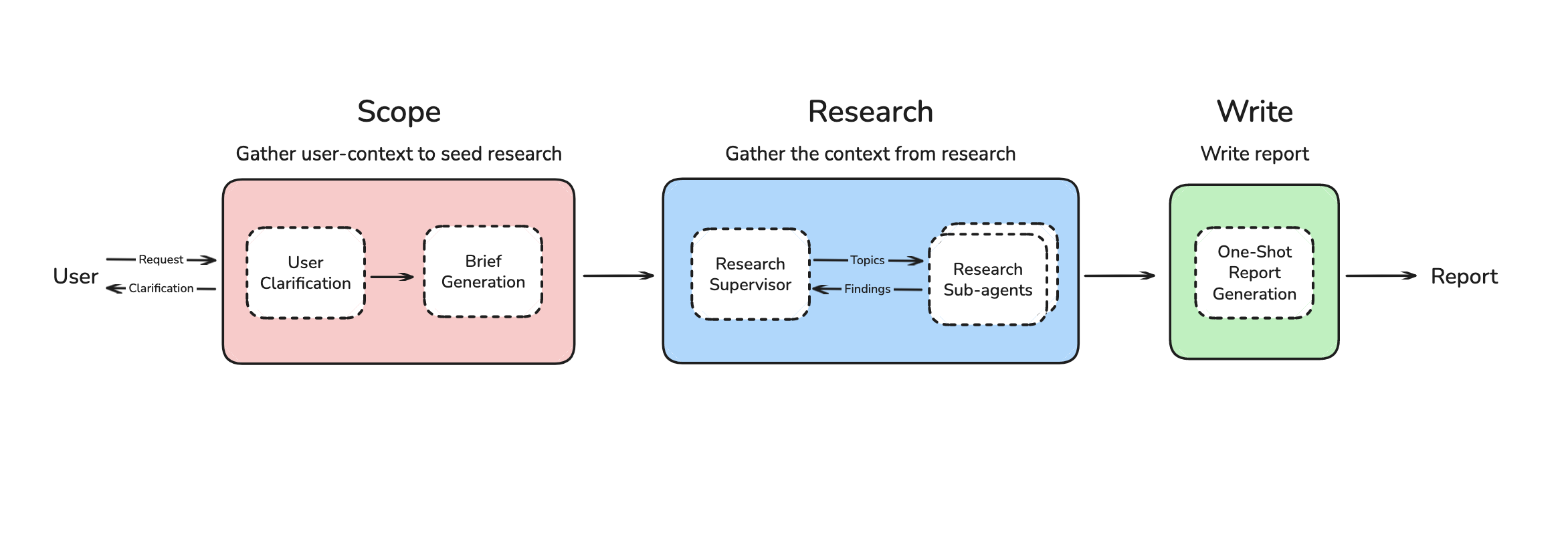

I moved to a multi-agent system, which allowed me to use tools and let the system flexibly plan the research strategy. But I designed it such that each sub-agent still wrote its own report section. This ran into a problem that Walden Yan of Cognition has called out: multi-agent systems are hard because the sub-agents often don’t communicate effectively. Reports were still disjoint because my sub-agents wrote sections in parallel.

This is one of the main points of Hyung’s talk: we often fail to remove all the structure we add as we update our methods. In my case, I moved to an agent, but still was forcing each agent to write part of the report in parallel.

I moved writing to a final step. The system could now flexibly plan the research strategy, use multi-agent context gathering, and write the report in one-shot based on the collected context. It scores a 43.5 on deep research bench (top 10), which is not bad for a small open source effort (and close to agents that use RL or benefit from much larger-scale efforts).

Lessons

AI engineering can benefit from some simple lessons drawn from Chung’s talk:

- Understand your application structure

- Re-evaluate structure as models improve

- Make it easy to remove structure

On the first point, consider what LLM performance assumptions are baked into the design of your application. For my initial workflow, I avoided tool calling because (at the time) it was not reliable. This was no longer true a few months later! Jared Kaplan (co-founder of Anthropic) recently made the point that it can even be beneficial to “build things that don’t quite work” yet because the models will catch up (often quickly).

On the second point, I was a bit slow to re-evaluate my assumptions as tool calling improved. And, on the final point, I agree with Walden (Cognition) and Harrison (LangChain) that agent abstractions can pose risk because they can make it harder remove structure. I still use a framework (LangGraph) for its useful general features (e.g., checkpointing), but stick to its low-level building blocks (e.g., nodes and edges) that I can easily (re-)configure.

The design philosophy for building AI applications is in its infancy. Still, as Hyung said, it is helpful to focus on the driving force that we can predict: model will get much better. Designing AI applications to take advantage of this will probably be the most important thing.

Credits

Thanks to Vadym Barda for initial evals, MCP support, and helpful discussion. Thanks to Nick Huang for work on the multi-agent implementation as well as Deep Research Bench evals.