Context Engineering for Agents

TL;DR

Agents need context to perform tasks. Context engineering is the art and science of filling the context window with just the right information at each step of an agent’s trajectory. In this post, I group context engineering into a few common strategies seen across many popular agents today.

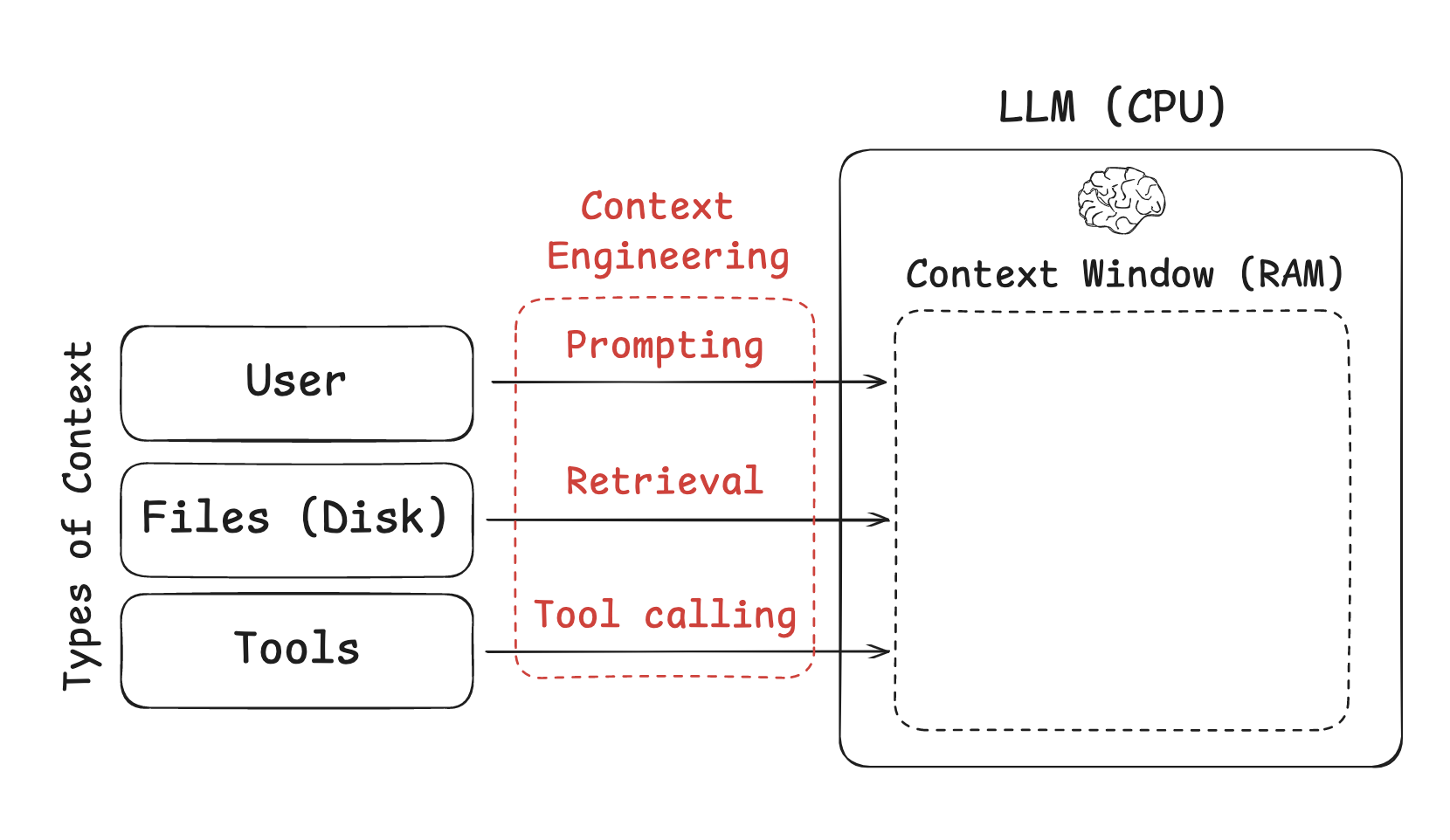

Context Engineering

As Andrej Karpathy puts it, LLMs are like a new kind of operating system. The LLM is like the CPU and its context window is like the RAM, serving as the model’s working memory. Just like RAM, the LLM context window has limited capacity to handle various sources of context. And just as an operating system curates what fits into a CPU’s RAM, “context engineering” plays a similar role. Karpathy summarizes this well:

[Context engineering is the] ”…delicate art and science of filling the context window with just the right information for the next step.”

What are the types of context that we need to manage when building LLM applications? Context engineering is an umbrella that applies across a few different context types:

- Instructions – prompts, memories, few‑shot examples, tool descriptions, etc

- Knowledge – facts, memories, etc

- Tools – feedback from tool calls

Context Engineering for Agents

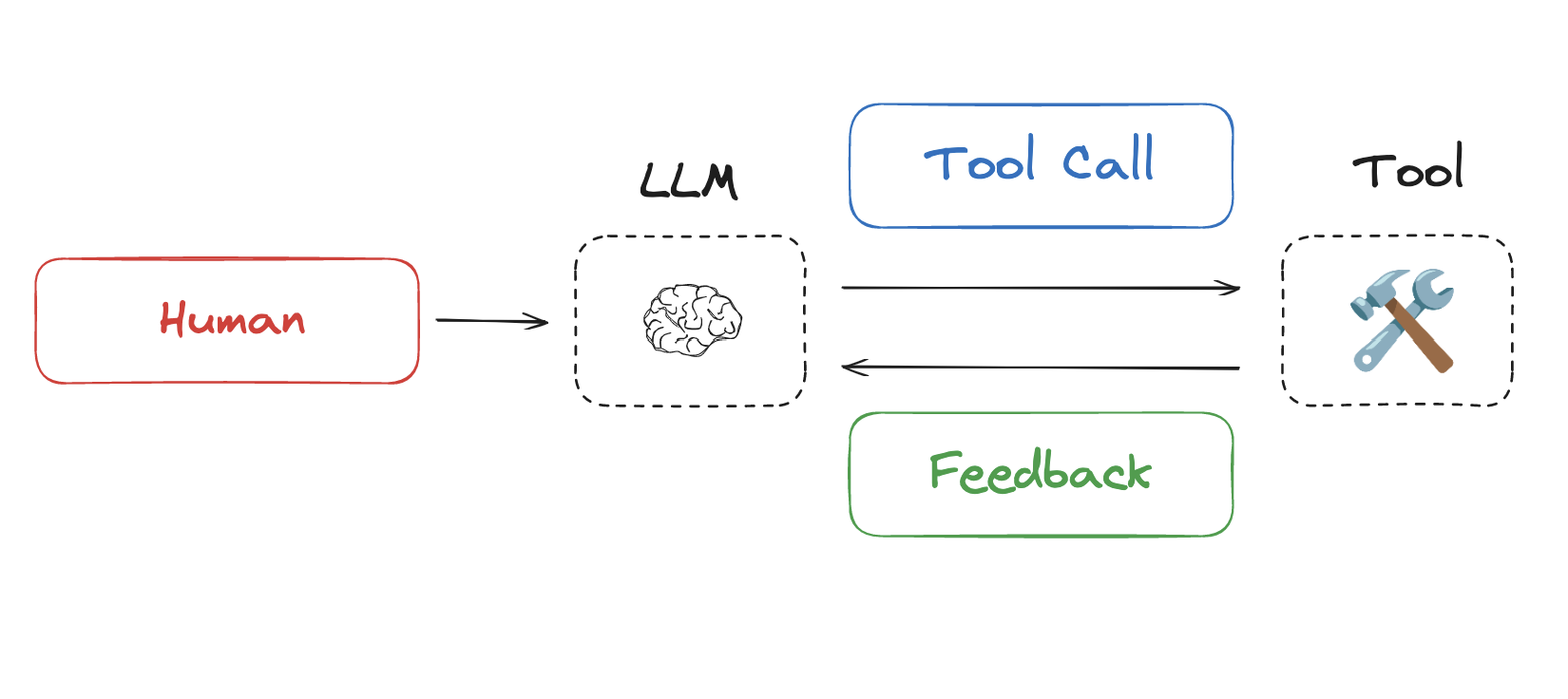

This year, interest in agents has grown tremendously as LLMs get better at reasoning and tool calling. Agents interleave LLM invocations and tool calls, often for long-running tasks.

However, long-running tasks and accumulating feedback from tool calls mean that agents often utilize a large number of tokens. This can cause numerous problems: it can exceed the size of the context window, balloon cost / latency, or degrade agent performance. Drew Breunig nicely outlined a number of specific ways that longer context can cause perform problems, including:

- Context Poisoning: When a hallucination makes it into the context

- Context Distraction: When the context overwhelms the training

- Context Confusion: When superfluous context influences the response

- Context Clash: When parts of the context disagree

With this in mind, Cognition called out the importance of context engineering:

“Context engineering” … is effectively the #1 job of engineers building AI agents.

Anthropic also laid it out clearly:

Agents often engage in conversations spanning hundreds of turns, requiring careful context management strategies.

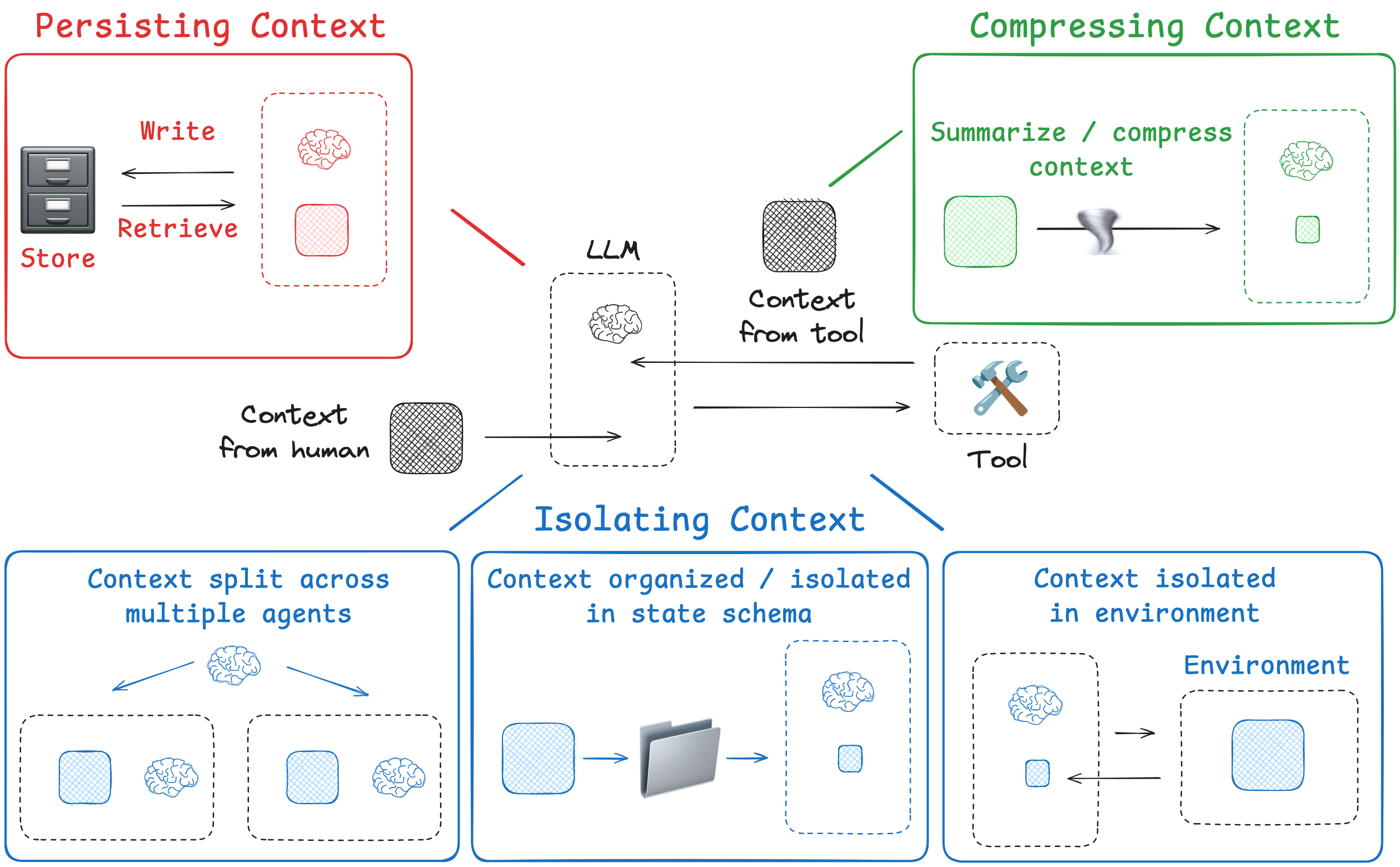

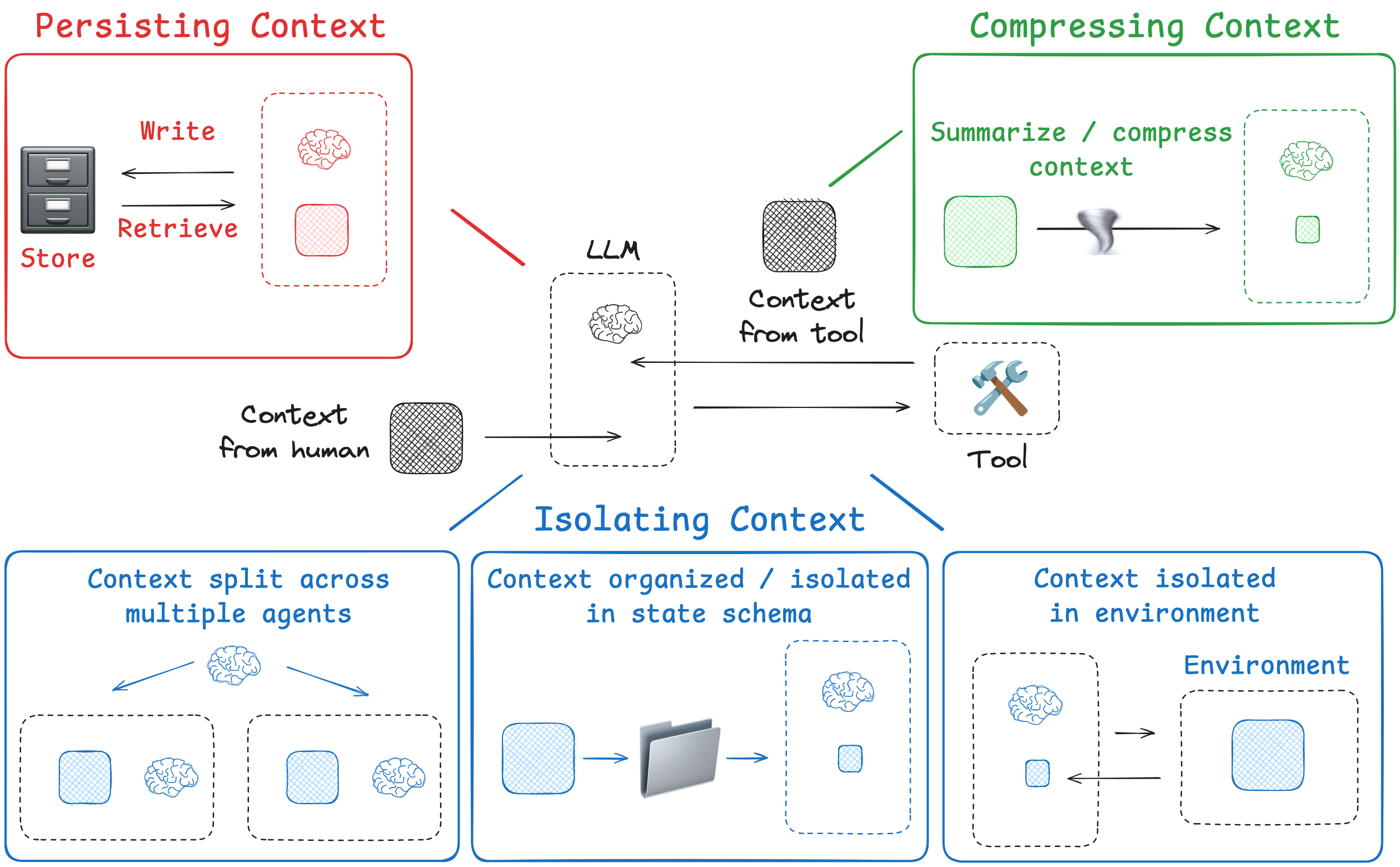

So, how are people tackling this challenge today? I group approaches into 4 buckets — write, select, compress, and isolate — and give some examples of each one below.

Write Context

Writing context means saving it outside the context window to help an agent perform a task.

Scratchpads

When humans solve tasks, we take notes and remember things for future, related tasks. Agents are also gaining these capabilities! Note-taking via a “scratchpad” is one approach to persist information while an agent is performing a task. The central idea is to save information outside of the context window so that it’s available to the agent. Anthropic’s multi-agent researcher illustrates a clear example of this:

The LeadResearcher begins by thinking through the approach and saving its plan to Memory to persist the context, since if the context window exceeds 200,000 tokens it will be truncated and it is important to retain the plan.

Scratchpads can be implemented in a few different ways. They can be a tool call that simply writes to a file. It could also just be a field in a runtime state object that persists during the session. In either case, scratchpads let agents save useful information to help them accomplish a task.

Memories

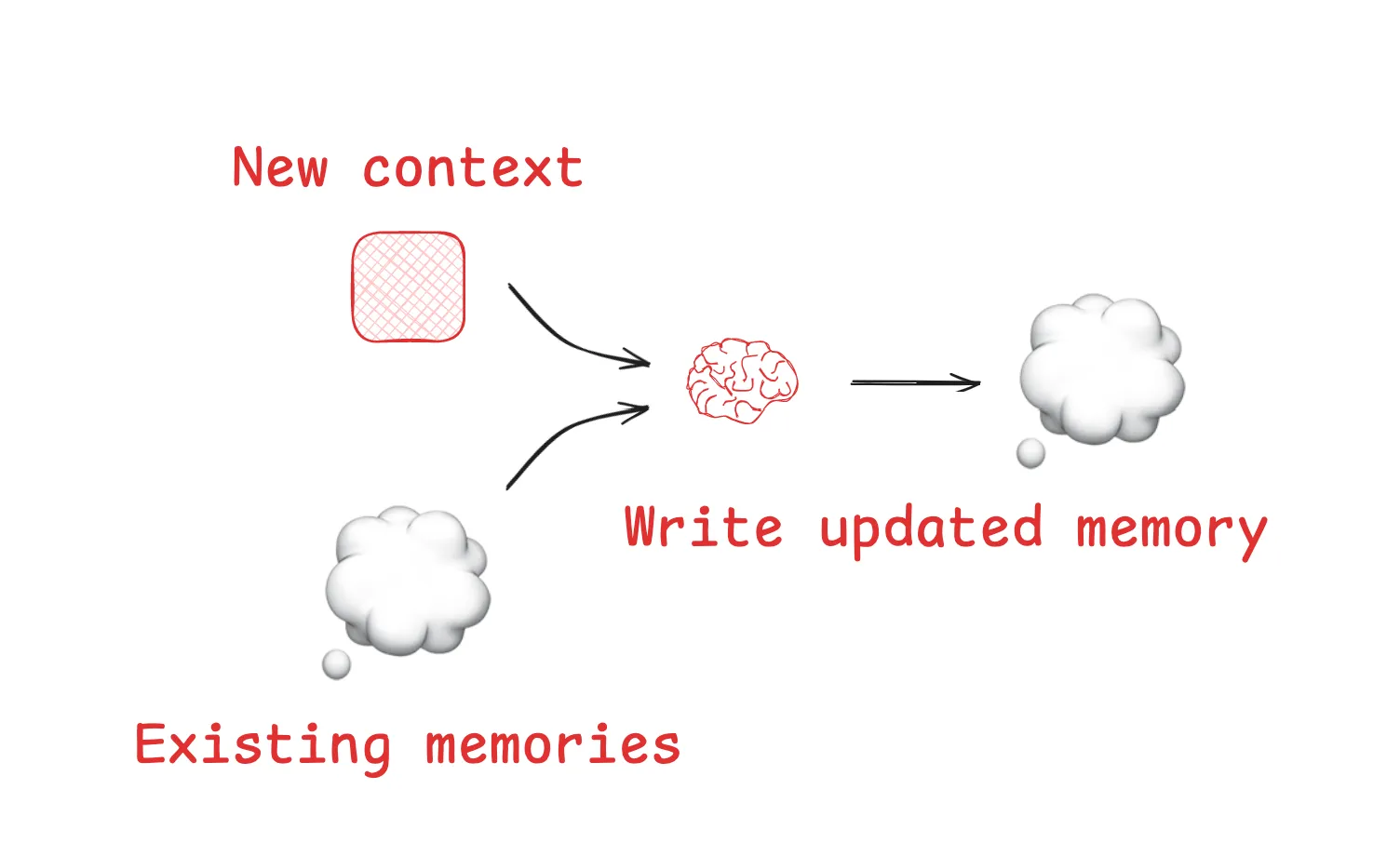

Scratchpads help agents solve a task within a given session, but sometimes agents benefit from remembering things across many sessions. Reflexion introduced the idea of reflection following each agent turn and re-using these self-generated memories. Generative Agents created memories synthesized periodically from collections of past agent feedback.

These concepts made their way into popular products like ChatGPT, Cursor, and Windsurf, which all have mechanisms to auto-generate long-term memories based on user-agent interactions.

Select Context

Selecting context means pulling it into the context window to help an agent perform a task.

Scratchpad

The mechanism for selecting context from a scratchpad depends upon how the scratchpad is implemented. If it’s a tool, then an agent can simply read it by making a tool call. If it’s part of the agent’s runtime state, then the developer can choose what parts of state to expose to an agent each step. This provides a fine-grained level of control for exposing scratchpad context to the LLM at later turns.

Memories

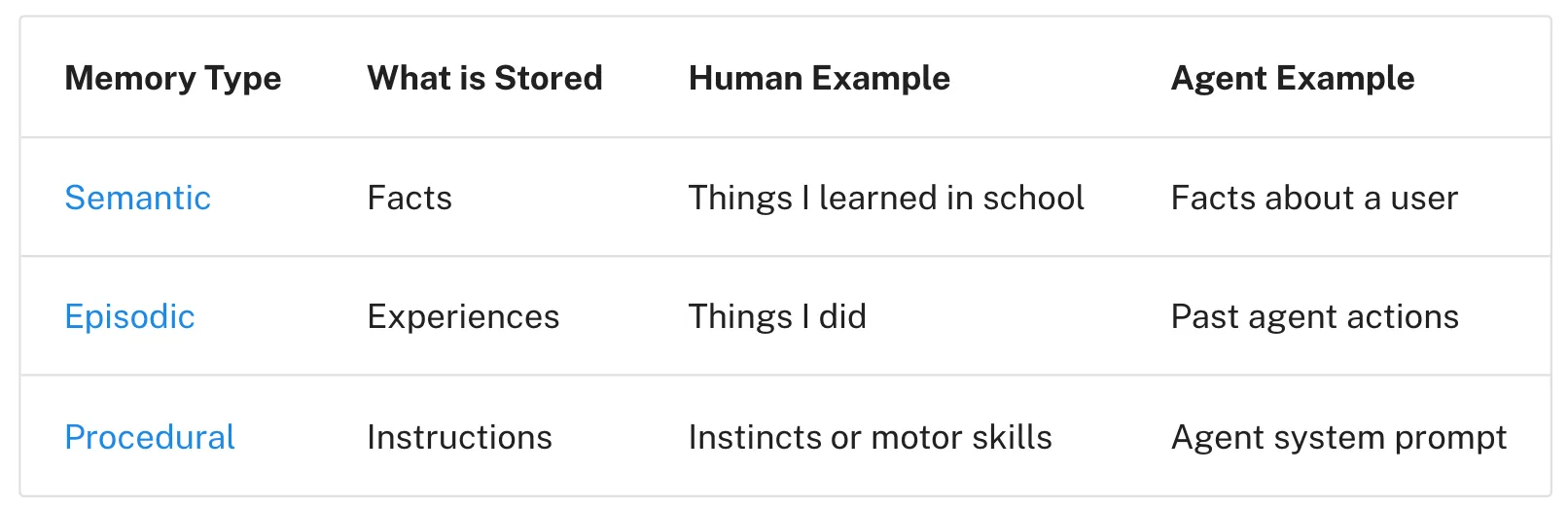

If agents have the ability to save memories, they also need the ability to select memories relevant to the task they are performing. This can be useful for a few reasons. Agents might select few-shot examples (episodic memories) for examples of desired behavior, instructions (procedural memories) to steer behavior, or facts (semantic memories) give the agent task-relevant context.

One challenge is ensuring that relevant memories are selected. Some popular agents simply use a narrow set of files that are always pulled into context. For example, many code agent use files to save instructions (”procedural” memories) or, in some cases, examples (”episodic” memories). Claude Code uses CLAUDE.md. Cursor and Windsurf use rules files.

But, if an agent is storing a larger collection of facts and / or relationships (e.g., semantic memories), selection is harder. ChatGPT is a good example of a popular product that stores and selects from a large collection of user-specific memories.

Embeddings and / or knowledge graphs for memory indexing are commonly used to assist with selection. Still, memory selection is challenging. At the AIEngineer World’s Fair, Simon Willison shared an example of memory selection gone wrong: ChatGPT fetched his location from memories and unexpectedly injected it into a requested image. This type of unexpected or undesired memory retrieval can make some users feel like the context window “no longer belongs to them”!

Tools

Agents use tools, but can become overloaded if they are provided with too many. This is often because the tool descriptions can overlap, causing model confusion about which tool to use. One approach is to apply RAG (retrieval augmented generation) to tool descriptions in order to fetch the most relevant tools for a task based upon semantic similarity. Some recent papers have shown that this improves tool selection accuracy by 3-fold.

Knowledge

RAG is a rich topic and can be a central context engineering challenge. Code agents are some of the best examples of RAG in large-scale production. Varun from Windsurf captures some of these challenges well:

Indexing code ≠ context retrieval … [We are doing indexing & embedding search … [with] AST parsing code and chunking along semantically meaningful boundaries … embedding search becomes unreliable as a retrieval heuristic as the size of the codebase grows … we must rely on a combination of techniques like grep/file search, knowledge graph based retrieval, and … a re-ranking step where [context] is ranked in order of relevance.

Compressing Context

Compressing context involves retaining only the tokens required to perform a task.

Context Summarization

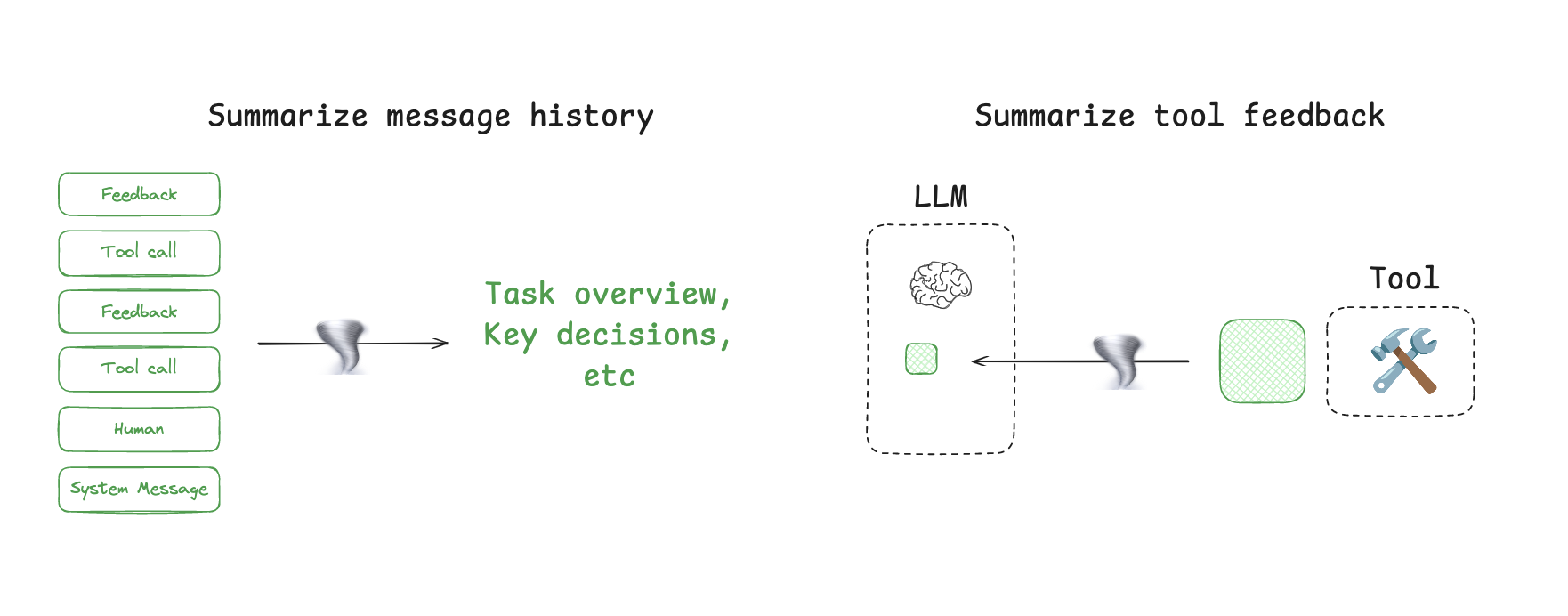

Agent interactions can span hundreds of turns and use token-heavy tool calls. Summarization is one common way to manage these challenges. If you’ve used Claude Code, you’ve seen this in action. Claude Code runs “auto-compact” after you exceed 95% of the context window and it will summarize the full trajectory of user-agent interactions. This type of compression across an agent trajectory can use various strategies such as recursive or hierarchical summarization.

It can also be useful to add summarization at points in an agent’s design. For example, it can be used to post-process certain tool calls (e.g., token-heavy search tools). As a second example, Cognition mentioned summarization at agent-agent boundaries to reduce tokens during knowledge hand-off. Summarization can be a challenge if specific events or decisions need to be captured. Cognition uses a fine-tuned model for this, which underscores how much work can go into this step.

Context Trimming

Whereas summarization typically uses an LLM to distill the most relevant pieces of context, trimming can often filter or, as Drew Breunig points out, “prune” context. This can use hard-coded heuristics like removing older messages from a message list. Drew also mentions Provence, a trained context pruner for Question-Answering.

Isolating Context

Isolating context involves splitting it up to help an agent perform a task.

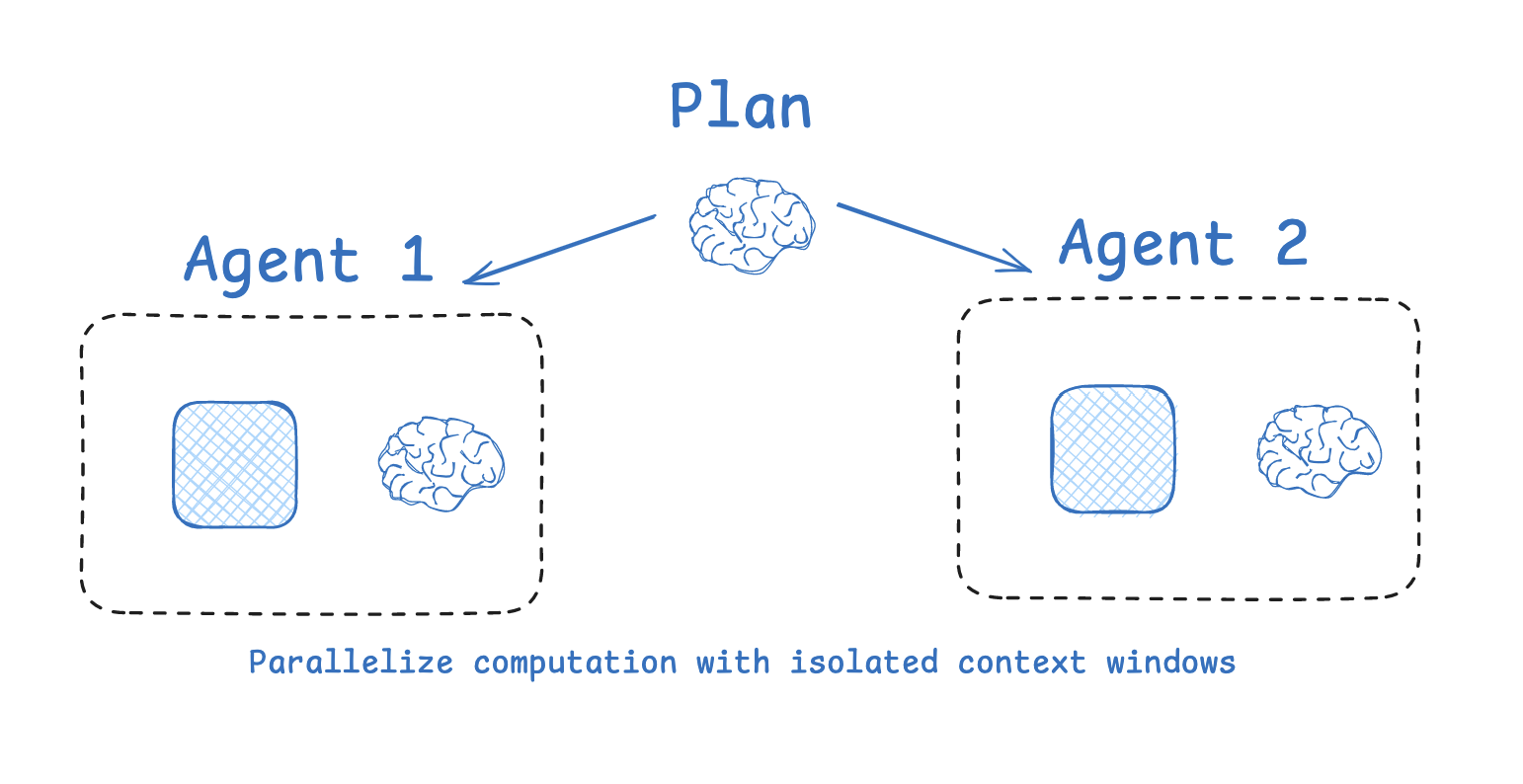

Multi-agent

One of the most popular ways to isolate context is to split it across sub-agents. A motivation for the OpenAI Swarm library was “separation of concerns”, where a team of agents can handle sub-tasks. Each agent has a specific set of tools, instructions, and its own context window.

Anthropic’s multi-agent researcher makes a case for this: many agents with isolated contexts outperformed single-agent, largely because each subagent context window can be allocated to a more narrow sub-task. As the blog said:

[Subagents operate] in parallel with their own context windows, exploring different aspects of the question simultaneously.

Of course, the challenges with multi-agent include token use (e.g., up to 15× more tokens than chat as reported by Anthropic), the need for careful prompt engineering to plan sub-agent work, and coordination of sub-agents.

Context Isolation with Environments

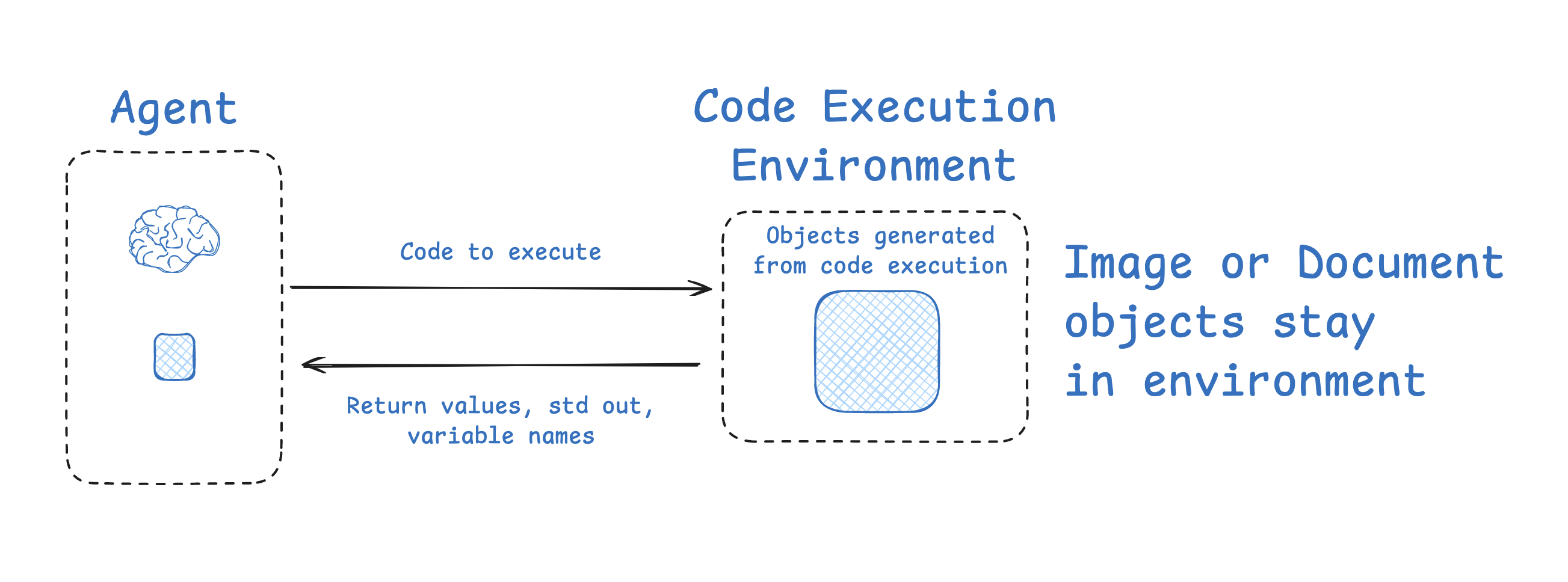

HuggingFace’s deep researcher shows another interesting example of context isolation. Most agents use tool calling APIs, which return JSON objects (tool arguments) that can be passed to tools (e.g., a search API) to get tool feedback (e.g., search results). HuggingFace uses a CodeAgent, which outputs code that contains the desired tool calls. The code then runs in a sandbox. Selected context (e.g., return values) from the tool calls is then passed back to the LLM.

This allows context to be isolated from the LLM in the environment. Hugging Face noted that this is a great way to isolate token-heavy objects in particular:

[Code Agents allow for] a better handling of state … Need to store this image / audio / other for later use? No problem, just assign it as a variable in your state and you [use it later].

State

It’s worth calling out that an agent’s runtime state object can also be a great way to isolate context. This can serve the same purpose as sandboxing. A state object can be designed with a schema (e.g., a Pydantic model) that has fields that context can be written to. One field of the schema (e.g., messages) can be exposed to the LLM at each turn of the agent, but the schema can isolate information in other fields for more selective use.

Conclusion

Patterns for agent context engineering are still evolving, but we can group common approaches into 4 buckets — write, select, compress, and isolate —:

- Writing context means saving it outside the context window to help an agent perform a task.

- Selecting context means pulling it into the context window to help an agent perform a task.

- Compressing context involves retaining only the tokens required to perform a task.

- Isolating context involves splitting it up to help an agent perform a task.

Understanding and utilizing these patterns is a central part of building effective agents today.